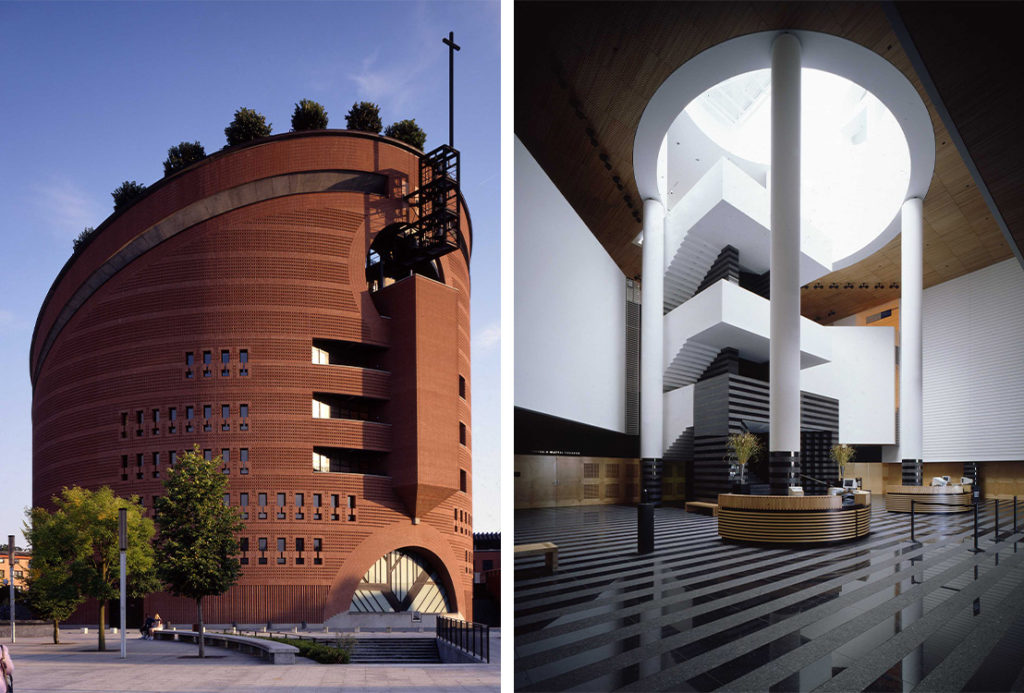

Although he began his career by designing individual houses for friends, enabling him to hone his language, Mario Botta soon felt his work was too limited. Breaking out of this mono-function in the 1980s, he took an ambitious turn towards architecture for public use. Since then, he has continued to venture into building projects with diverse functions, installed on different continents. The Tinguely Museum in Basel, the Cathédrale de la Résurrection in Evry, the Martin Bodmer Foundation in Geneva, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Rigi Kaltbad, the Campari headquarters in Milan, the Bechtler Museum in North Carolina, the Lu Xun Academy campus in Shenyang and the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art in Japan – these are just a few of the many examples of Mario Botta’s creative spirit.

Although the buildings are used for different purposes, the Ticino architect’s style is clearly evident. The use of natural materials, geometric shapes and lines, the repetition of rhythms, the interplay of voids and the incorporation of nature distinguish his projects. Mario Botta makes a point of anchoring buildings in their environment, whether typographically, aesthetically or culturally speaking.

While he travels the world to create his architectural works, it’s in his native Ticino that Mario Botta has decided to set up his studio. In an open space of almost 700 square meters of travertine and concrete in Mendrisio, models of current projects, photos of recent inaugurations and pieces from past collaborations mingle. Meet Mario Botta in his studio.

NOW Village : You studied in Italy, taught in Switzerland, built all over the world, opened a branch in Lugano, only to relocate a few years later here in Mendrisio. Why are you so attached to your home town?

Mario Botta : I’m deeply convinced that it’s better and, above all, simpler to work from home, to be in your own territory. I could have set up my offices in America or Asia, but an architect never works for himself, but to meet the needs of an environment. So you need to know the environment well.

With buildings in the USA, Japan, France, the Netherlands, Italy and other countries around the world, how do you adapt your thinking when you change regions?

I’ve never touched a pencil to start a project without knowing the geographical location of the site. So I start by questioning the landscape, the current context of the region, the history of the place, its rhythms and myths, and then develop a general vision of the social fabric. In the end, the answers I seek are already transcribed by nature. A critical reading of the context leads to solutions to all my questions.

Does this mean that you spend a certain amount of time in a city to immerse yourself in it?

Each case is unique, sometimes I need to stay in a place for a long time, sometimes the vision is so intense that it stays with me and I can work with my memory. There aren’t really any fixed rules. But from time to time I feel a strong emotional attachment for no particular reason. It’s a bit like falling in love!

And coming back to Europe, is Switzerland ready to move away from historical architectural codes?

Absolutely not! But it’s not up to Switzerland to break out of its codes. It’s up to its architects to come up with new ones! In a broader sense, people have to respond to new demands and changes in the context of the state, i.e. geographically, socially, morally and economically, and adapt each area. This is what makes a country evolve. The Switzerland I knew as a child is not the Switzerland I worked in as an architect ten years ago, and even less the Switzerland I know today. Switzerland is a reality in which I live and which I love. But a reality that is constantly evolving with global events, such as pandemics, climate change, energy problems and so on. It’s up to me, as an architect, to find solutions.

Have your codes changed too?

Yes, my language has also evolved over the years. I’m strongly influenced by the context, whether it’s positive or negative. As an architect I have to react to new living conditions!

You’ve worked with Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn and Scarpa Carlo. How did they influence you?

Le Corbusier was to architecture what Einstein was to physics. Whether you like or dislike his style, you have to take it into account to understand the transformation of the 20th century. The common thread running through all his work is his ability to solve the problems of living in a society at war. In his teaching, he provided the first technical guidelines for meeting new needs and looking to the future of urban planning. Today’s instruments and materials have evolved, but his principles remain undeniably modern.

Louis Kahn belongs to another generation of architects, younger than Le Corbusier. In particular, he worked on the principle of the territory of memory, always trying to get to the roots of problems and decipher what was at stake for the community. In other words, to understand existing forces and anticipate the future, he started from the experience of past generations.

The third is Scarpa Carlo, my teacher in Venice, who had this ability to let the simplest materials express themselves. So, alongside the noblest materials like gold, he also gave dignity to the poorest metals, stone and wood. It was an invaluable lesson that I continue to apply in my work!

You in turn decided to pass on your knowledge by founding the Accademia di architettura di Mendrisio (AAM). How does its teaching differ from other architecture institutions?

Unlike other schools that focus on scientific training, I wanted to base my teaching on human sciences subjects. The technical part is of course important, but I believe that today’s architect must be aware of how the world has evolved from a cultural and historical point of view, while at the same time having a human conscience. To use the term again, the architect must know the territory of memory: in other words everything that history has produced and that influences today’s world. I exist because I remember, and not just the events, but also the history of feelings and emotions.

Is this also why you have worked on so many cultural and religious sites?

Yes, that’s one of the reasons, since both speak of the spirit, and therefore of the territory of memory, and have aspects that are incommensurable with rational analysis. The church is a place of prayer and the museum a place of transmission. But in both we find the traditions of life. That said, I’d rather build churches than any other human activity!

What role does light play in your designs?

Without light, there is no architecture. Light creates spaces. The role of the architect is to tame it according to the needs of the room and its evolution. Even if light follows the solar cycle, it changes at every moment of the 365 days of the year!

You said, and I quote: “Architects need time and experimentation to perfect their skills. So there’s no need to be in a hurry“. Is the pace too fast for creativity?

I don’t know if it’s going too fast, but that’s the current pace. We didn’t choose to live in the 1940s! In the end, everyone takes stock and prioritises certain things. Personally, I’m a monomaniac and find peace in my pencil.

To talk about developments in the 21st century, do you use new technologies or innovative materials in your work?

I don’t believe in the rhetoric of technology. These days, I get the impression that whenever technology is mentioned, the context is necessarily positive. I’m not stupid to think that technological development is bad, but like any tool, it can be used well or badly. At the moment, I think the tendency is to use it badly. Take artificial intelligence, for example. Obviously as an instrument it is more powerful than the natural one. But it is promoted without mentioning the possible abuses and dangers of this infinite memory.

You’ve designed buildings as well as furniture and decorative items. Do you see yourself as both an architect and a designer?

In my opinion, the two professions are one and the same, because the reasoning behind the design of a building or a table is the same. The difficulty is comparable, even if the scale and the tools are different. Like architects, designers have worked to solve the problems of their time and have produced extraordinary prototypes that have gone down in history. Take Gerrit Rietveld’s colourful blue/red/yellow chair, for example, which turned furniture trends on their head!

And in conclusion, of all your achievements, which is your favourite?

The next one, of course!

Read also: our article on the Museum Tinguely in Basel, designed by Mario Botta.