Alexander Calder’s kinetics, Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made, Auguste Herbin’s pictorial alphabet, Walter Bodmer’s wires, the spirit of Dada, the questioning of academism and homage to the abstract avant-garde, while defining himself as a realist, make up Jean Tinguely’s style and aspirations. Starting from geometric abstraction to go beyond the static state of his creations, he is undeniably attached to the principle of movement. This is the very essence of his works, which makes them both infinite and ephemeral. From the water wheels in the Basel streams to the machines that were the precursors of the steampunk style, Jean Tinguely’s life in gears.

The future sculptor of scrap metal and recycling artist was born in Freiburg in 1925, before quickly moving to Basel, in the lively district of Gundelding. Calling himself a Baseler or a Freiburger, he became interested in the world that was then turned upside down by world conflicts, frequenting the circles of political refugees and artists exiled in Switzerland. At the age of 15 he even tried to reach Albania to help the Greeks in their resistance against the Italian fascists, but unluckily he was arrested before he had even left Ticino. Back home! His second passion is forests, not to admire nature, but to make it interact with his constructions. Thus, without even knowing it, he realized the first installations in a style that would earn him several invitations to World Fairs. But let’s not be too hasty, at that time, Jean only set up a series of hydraulic wheels in a small stream, whose current activated a system of hammers that hit old cans and other waste. A sound suite not necessarily very melodic, but which undeniably shatters the Swiss peace. Water, noise and movement will remain faithful leitmotifs of Jean Tinguely’s poetic mechanics for a long time to come!

From Basel to Paris

In perpetual conflict with his parents and not very assiduous at school, Jean Tinguely began an apprenticeship as a decorator at Globus in 1941. His shop windows are different from the others, more carefree, dynamic and rotating, they come to life thanks to metal wheels. But the lack of punctuality and discipline of their creator will earn him an immediate dismissal. He still finished his training, but at Joos Hutter. It was Hutter who urged the young apprentice to attend regular classes at the Kunstgewerbeschule. “It is the new shock of contemporary art and the discovery of art in itself, the presence of art” will say one day the Basler of his art school. If he is naturally passionate about the Bauhaus, Dadaism and the work of Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Duchamp or Paul Klee, the teaching of classical art does not interest him. That said, it will have a fundamental role on the whole of his work. How is this possible? Simply by refraction. If he works ardently on the oil paintings, scraping the canvas until it wears out, he is unable to decide when they are finished. He constantly wants to put back a layer or on the contrary to remove the still soft color! A solution to this petrification? The movement! Then begins the fanaticism of mechanical sculptures in action, turbulence, swinging, agitation, effervescence and shaking. It is thus with this principle as philosophical as kinetic, that the artist, freshly married with one of his classmates, Eva Aeppli, settled in Paris in 1952.

In the end, “working with movement means organizing the ephemeral,” as Jean Tinguely explained.

Parisian meta-matics

Although his frustration with static art grew, Jean Tinguely was not fundamentally opposed to it. On the contrary, he relied on it to create his new mobile sculptures. Thus, in the 1950s, several series were created, such as Méta-Malevitch, Méta-Herbin or Méta-Kandinsky. You will have guessed, as their name indicates, the abstract compositions with geometrical references are put in movement by mechanisms. The pieces become alive! But gradually the reference to art gives way to pure mechanics. It is decided, the sculptor wants to work on the disorder of machines! Even his manifesto, Für Statik (For the static) begins with : Everything moves, there is no immobility. For the little anecdote, the artist would have launched nearly 150 000 leaflets of it from a plane over Düsseldorf in 1959! Intrepid, isn’t it? But let’s go back a few years, to better understand the universe that Jean Tinguely is making.

He is of course not the first to look at sculpture in motion. Moreover, in 1955 a large exhibition was dedicated to mobile sculptures that brought together, among others, the kinetic works of Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Calder, Yaacov Agam, Jesús-Rafael Soto and Jean Tinguely at the Denise René gallery, but that’s another story. Back to Tinguely art. He is not the first to use recycled materials in his creations, ahead of Arman, César or art brut. He is however the first to combine these two trends to create a unique and so recognizable style. Thus, contrary to the academicism of art and the cult of the new, he makes works from old objects, which have already fulfilled their original mission or which reveal themselves in a completely aberrant use. Recycling before it becomes mainstream! Since noise is an undeniable component of any mechanism, Jean Tinguely decided to make it a facet of his art in its own right. Thus, rather than masking it, he accentuated it, making it even more spectacular. His creations groan, crackle, sizzle, emit odors or smoke, shake and sigh – in short, a joyous carnival bazaar or Basel carnival, so dear to Tinguely. In short, machines that are totally useless in the era of the development of the machinery of the thirty glorious years! What audacity!

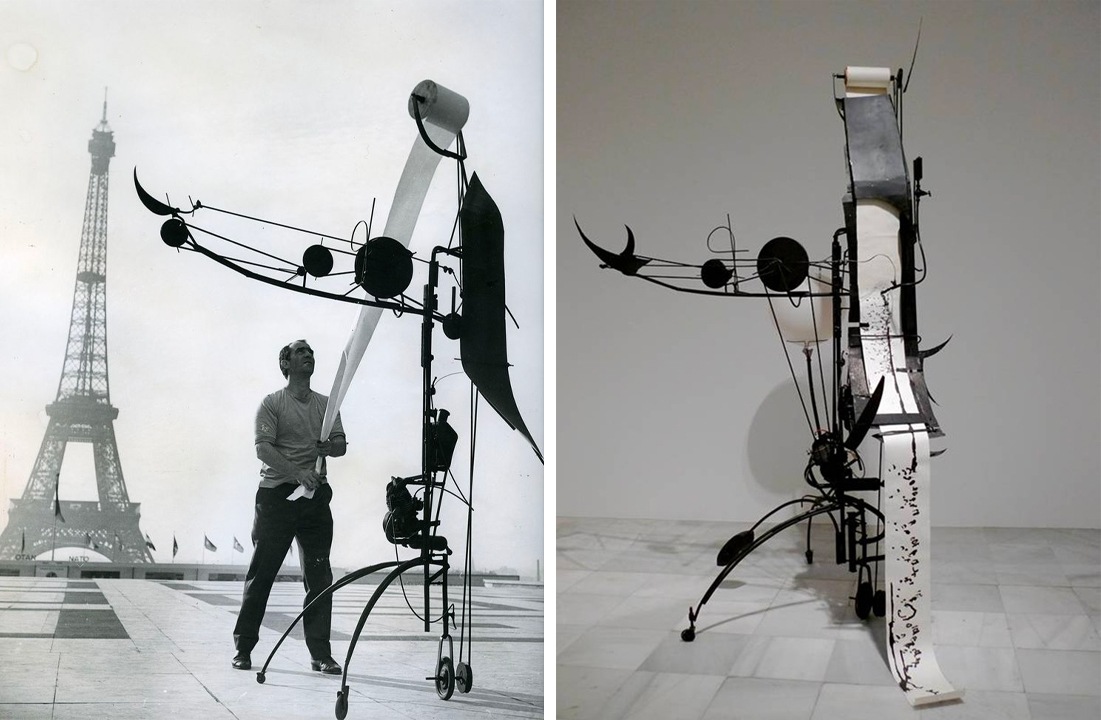

If initially his machines are art simply by their existence, they begin to produce art themselves. Tinguely created a whole series of these scrap metal artists called Méta-matics. The most famous of these is probably number 17, which attracted attention at the 1959 Paris Biennale. The drawings were then freely distributed to all visitors. Today, one would ask whether these sheets are art, and if so, by whom, Tinguely or the machine, but at the time it was simply a fun and light-hearted attraction. Moreover, the sculptor made other absurd demonstrations both inside the Museum of Modern Art and in the courtyard (and yes, you have certainly seen those pictures of Tinguely with a toilet paper roll camera with a view of the Eiffel Tower!) which attracted the curiosity of the spectators and the wrath of the other exhibitors. The artist went even further in 1960 during his happening in the garden of the MoMA in New York: a machine made of salvaged materials from the dumps and flea markets of New Jersey, whose sole purpose was to self-destruct. Certainly, in a long way of 27 minutes and very spectacular with smoke, sparks and roars, but it is all the same a suicide in the time of the technicization of the society. Eternal machines that will outlive man, they said, but in the end Tinguely shows that a machine can also die! The work is ephemeral, return to the garbage assured. He will make others, perhaps to reconcile himself with technology or to prove the possible end of machines, following the trauma experienced as a teenager during the bombing in Basel? Or simply to question whether technology could have been something else?

Moreover, in the same year, on October 27, 1960, a manifesto of the New Realists was signed by a group of artists, including Jean Tinguely, Arman, Yves Klein and a certain Niki de Saint Phalle.

Niki and Jean

While they met for the first time in 1956, the two artists have maintained a lifelong love and artistic relationship. He plays with his mechanical scrap metal, she designs gigantic sculptures with round, almost childlike shapes. They begin by influencing each other. Mechanisms appear in Niki’s sculptures, Jean creates the giant Eureka for the 1964 Swiss National Exhibition, which marks the beginning of the sculptor’s black painted works. If the different components are less visible, the movement is more uniform. A dazzling success for this useless machine with a paradoxical name, which is now installed at the Zürichhorn! Then began a true collaboration between the two artists, whose joint projects flourished. Hon at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1966, Le Paradis Fantastique for the 1967 World Fair, the Igor Stravinsky Fountain in Paris in 1983 and the monumental work in Milly-la-Forêt, Cyclop, to name but a few. Bonnie & Clyde of contemporary sculpture!

Various international exhibitions and large-scale projects followed one another for Jean Tinguely, but the last artistic turning point was surely the Mengele-Danse macabre. In 1985, the artist woke up from a coma after a heart operation in Bern, but the following year he witnessed a fire on his neighbors’ farm in Neyruz. A few days later, he extracted the remains of burnt out beams and machinery to create a work measuring three by four and a half meters. The theme of death thus becomes more explicit.

Jean Tinguely’s last journey is symbolically on board the Moscow Death Safari on Red Square. Made from a Renault car, this strange vehicle with giant gears and skulls is the apotheosis of the artist’s kinetic art. Movement in every sense of the word! Finally, after a last exhibition at the Kunst Haus Wien, the artist died in 1991 in Bern, following a heart attack.

The final tribute to this eccentric artist is paid by none other than Niki de Saint Phalle, who bequeathed almost 50 of his works to the Museum Tinguely, which opened in Basel in 1996. But it is in Freiburg that their two destinies will remain forever linked in the Espace Jean Tinguely – Niki de Saint Phalle.