A Childhood Between Politics and Philosophy

Germaine de Staël, born Anne-Louise-Germaine Necker on April 22, 1766, in Paris, came from an illustrious Swiss family. Her father, Jacques Necker, was a wealthy Genevan banker who became Louis XVI’s Minister of Finance, while her mother, Suzanne Curchod, was a Vaudois intellectual who hosted an influential literary salon.

From an early age, Germaine was immersed in the world of Enlightenment thought, frequenting leading intellectuals of the time such as Diderot, Buffon, and Abbé Raynal. Benefiting from an unconventional education for a young girl of her era, she developed remarkable erudition and a passion for politics and literature.

Entry into Aristocratic and Political Circles

In 1786, an arranged marriage was concluded, and she wed Éric Magnus de Staël-Holstein, the Swedish ambassador to France. This marriage granted her privileged access to the corridors of power. She quickly established her own literary salon in Paris, where she hosted influential figures such as La Fayette, Condorcet, and Talleyrand. Together, they had four children.

While leading these intellectual gatherings, she also began her career as a writer. A supporter of constitutional monarchy, she initially welcomed the French Revolution but was forced into exile in England in 1793 following the fall of Louis XVI and the rise of the reign of terror.

An Engaged Intellectual: Feminism and Abolitionism

Germaine de Staël was a staunch advocate of freedom in all its forms. A devoted reader of Rousseau and an admirer of the English model, she campaigned for a moderate republic and directly challenged the systemic prejudices of her time.

Her commitment to women’s rights was central to her work. Through her correspondence, essays, and novels, she advocated for women’s education and autonomy, denouncing their marginalization in society.

She was also a prominent abolitionist, influenced by her father’s positions. As early as the 1790s, she condemned the slave trade and published politically engaged short stories, such as Mirza or A Traveler’s Letter, The Story of Pauline, and Zulma, in which she criticized slavery and championed emancipation.

Exile in Coppet and Opposition to Napoleon

Initially fascinated by General Bonaparte, she quickly became one of his fiercest opponents. Her influence and critical spirit irritated Napoleon, who banished her from Paris in 1803 and prohibited her from publishing in France.

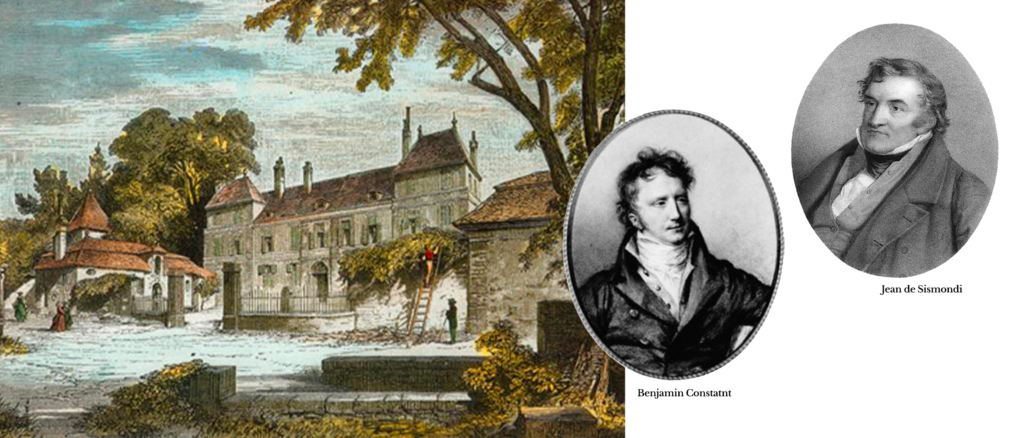

She sought refuge in her Château de Coppet, near Geneva, where she established a major intellectual hub. What later became known as the “Coppet Group” brought together leading writers and thinkers, including Benjamin Constant (her former companion) and Jean de Sismondi. Together, they debated new political models and advocated for the abolition of slavery.

Between stays in Coppet, she traveled extensively across Europe, particularly to Italy, Germany, and Russia, spreading Romantic ideals. Her book On Germany (1810), in which she celebrated Germanic culture, was banned by Napoleon, who saw it as a challenge to his authority.

Late Recognition and a Lasting Legacy

With Napoleon’s downfall in 1814, Madame de Staël was finally able to return to France. Her unwavering opposition to the Empire cemented her reputation as a major figure of liberal thought.

However, after years of exile and intellectual struggles, her health declined. She passed away on July 14, 1817, at the age of 51, leaving behind a vast body of work and a lasting influence.

A Free Spirit That Still Inspires Today

Today, Madame de Staël is recognized as a pioneer of feminism, liberalism, and abolitionism. Her Château de Coppet remains a symbol of independent thought and intellectual freedom.

Her fight did not end with her. Her son Auguste-Louis de Staël-Holstein and her former companion Benjamin Constant continued her campaign against slavery, actively working toward its abolition in the 1820s.

Through her audacity, independence, and commitment, the proud Romande Madame de Staël remains a timeless figure in the fight for freedom and progress.